She Climbed Kilimanjaro. But the Real Achievement: Keeping Her Phone Alive.

Extreme conditions require unusual measures to preserve gadgets and get online; 756 messages that won’t open

By Anupreeta Das

Nov. 8, 2019

MOUNT KILIMANJARO—At 13,800 feet on Africa’s highest mountain, as the nighttime temperature dipped and I drew my hot-water bottle closer, the following thoughts occurred in quick succession:

MOUNT KILIMANJARO—At 13,800 feet on Africa’s highest mountain, as the nighttime temperature dipped and I drew my hot-water bottle closer, the following thoughts occurred in quick succession:

Don’t quit now.

I was toasty in my sleeping bag. My iPhone, sitting on the tent floor, was not. How would I survive if my phone died on the mountain?

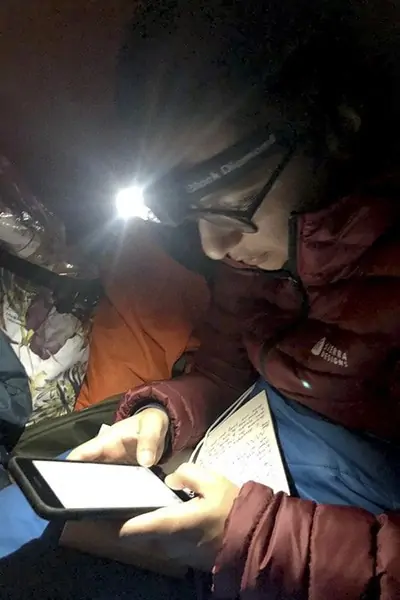

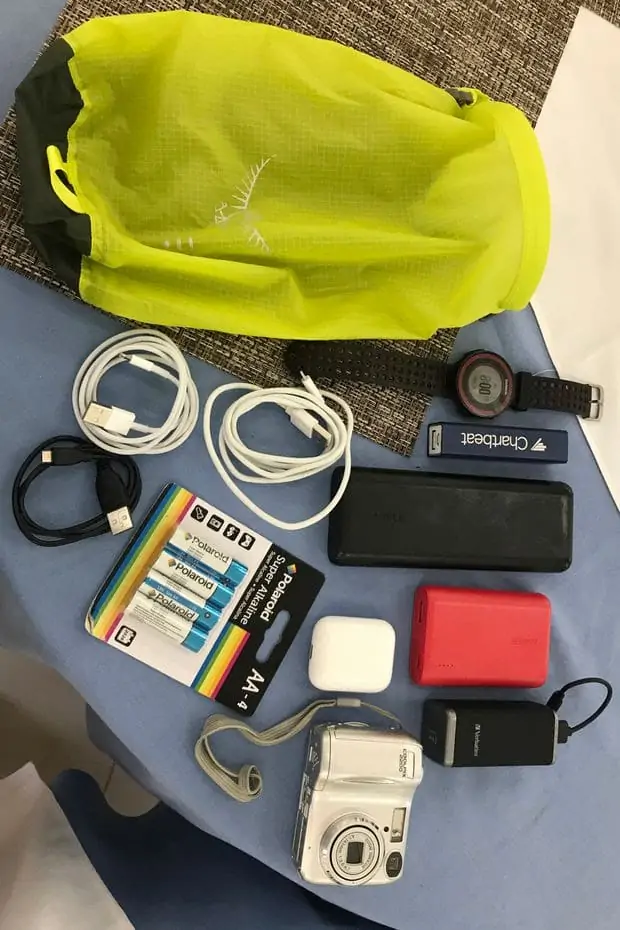

There was only one thing to do. I would have to spoon my phone. Then, feeling bad for all the other gadgets I had brought along on my weeklong quest to summit Kilimanjaro, I snuggled my smartwatch, my AirPods, two digital cameras, a headlamp, charging cables, three power banks and several dozen spare batteries inside my bag.

It was a little crowded.

I definitely could not have nested with my tech,” said Lilla Zuill, my tentmate, after several nights of watching me fuss over my gadgets, rather like a hen with mechanical eggs. “It was too uncomfortable,” she added, having tried it one night and woken up with a 1.3-pound portable battery charger on her. After that, she stuffed her tech inside hats and pockets instead.

Gadgets, especially smartphones and devices powered by lithium-ion batteries, respond poorly to extreme cold. They can freeze or develop glitches. Batteries drain alarmingly fast. (On day two, as we climbed from 11,550 feet to 12,540 feet, my phone’s battery went from 100% to 72%. In airplane mode.) The internet is packed with helpful hacks for climbing Kilimanjaro, the 19,341-foot volcano that is on the border of Tanzania and Kenya. How to keep your tech from freezing is a popular category of advice, with suggestions ranging from stuffing gadgets into spare socks with hand-warmer packs to taking backup devices.

“We’re addicted to our personal technology so let’s not have a philosophical discussion about going cold turkey on technology while on our Kilimanjaro climb,” wrote Eddie Frank, a longtime Kilimanjaro guide, in a blog post advising climbers on ways to stay connected, including buying a local SIM card.

On the mountain, temperatures can range from autumnal in the lower reaches to Arctic at the top. Summit night can be especially rough on batteries and screens. A woman from Hanover, Germany, on her way down, advised us to keep our phones and other gadgets in “the third of the six or so layers you will wear to the top so that body heat can keep the battery warm.”

My tech angst increased with the altitude. Accustomed to tracking and documenting my life via social media and apps—and conditioned to expect connectivity everywhere—I was half expecting to tweet, text and talk my way up to the “roof of Africa.” But 4G is spotty at best on the mountain, and nothing appears to drain a phone’s battery faster than searching for a signal in the cold. There would be no Instagramming from Kilimanjaro.

One morning, I saw that 756 messages had come in overnight, but they refused to download. For days, the little red bubble listing my unread messages was a circle of hell. Another morning, at around 12,870 feet, I woke up to find our guides and porters chatting on their cellphones. A cell tower was visible in the distance. When I turned off airplane mode, the first message that came through was a work-related text from a colleague.

Our group of four hikers had brought at least seven power banks, two solar chargers and dozens of batteries to charge multiple iPhones, smartwatches, digital cameras, headlamps, AirPods, one Kindle, a mobile hotspot, a satellite hotspot and an iPad.

Ms. Zuill had come especially prepared. A Bermudian lawyer with her own firm, she had packed enough gadgets to set up a mobile office, including a satellite hotspot that was supposed to allow her to talk, email, browse the web and even tweet. She also brought the iPad on the off-chance she could review legal documents.

It didn’t go as planned. Tweets sent recording our journey failed to post. The hotspot refused to work as advertised, requiring Ms. Zuill to walk around the campsite after dinner searching for an obstruction-free zone. Higher elevation proved more fruitful. “Suddenly, my office was a tent on the side of Mount Kilimanjaro,” Ms. Zuill said, after checking in with co-workers from 14,000 feet.

Eventually, I was forced to observe that I’d undertaken this adventure to disconnect from normal life and recharge myself rather than fretting about whether my tech was juiced or whether I could send a mountainside witticism or two via WhatsApp.

I abandoned my search for a phone connection. But here’s why I couldn’t let my iPhone die. It was my main camera, my alarm clock, my mirror in selfie mode, my flashlight, my electronic diary—and as I discovered, my pedometer even without a connection, allowing me to track my progress in miles walked, steps taken and floors climbed (64.3 miles, 157,631 steps, 883 floors).

The day we reached base camp, elevation 15,180 feet, I texted a colleague: “I will try to tweet from the mountain top.”

At 1:27 a.m., as we set off for Uhuru Peak, I dutifully stuffed my phone into the pocket of my fleece vest, the third of five layers, wondering how I would whip it out to take photos. It wouldn’t matter. For the next eight hours, I could think of nothing but setting one foot in front of the other, as the air grew thinner and the snow thicker. Dawn broke; photo opportunities were lost.

When I finally reached the top, my guide offered to take a photo to record my triumph. My phone still worked, but I forgot to check for a signal, let alone tweet from the peak, before it was time to go back down.