It is very common for people interested in climbing Kilimanjaro to ask whether it is dangerous to do so.

Like any outdoor adventure activity, climbing a mountain that is 19,341 feet tall definitely has elements of risk. But it shouldn’t deter you from booking a trip. In this post, we will examine how dangerous climbing Kilimanjaro is based on past studies.

HOW MANY DEATHS OCCUR ON MOUNT KILIMANJARO?

It is difficult to gauge just how dangerous it to climb Kilimanjaro because the number of fatalities is not known. Kilimanjaro National Park Authority (KINAPA) does not release data on Kilimanjaro related deaths. The reason is likely that the government feels it would negatively impact tourism.

However, a few years ago a study by Markus Hauser addressed this topic. In his paper, Deaths due to High Altitude Illness among Tourists Climbing Mount Kilimanjaro, Hauser studied autopsies of tourists who died while climbing Kilimanjaro from 1996 to 2003. Over those eight years, there were only 25 deaths total. Because autopsies are legally required on fatal incidences among tourists in Tanzania, Hauser’s fatality statistic is considered to be completely accurate.

Hauser concluded that the overall mortality rate was 13.6 deaths per 100,000 climbers. He stated that though altitude sickness occurred frequently among climbers, fatal cases were rare.

A look into the autopsy reports revealed that there were 17 males and eight females. The ages ranged from 29 to 74. The report states that the deaths were a result of High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) or High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE), pneumonia, trauma, and one from appendicitis.

Given that 20,000 tourists visited Kilimanjaro annually in the eight years that were studied in the paper, and there are nearly double the number of people climbing Kilimanjaro today, one would logically expect that the current number of deaths to be nearly double. With approximately 40,000 people climbing Kilimanjaro every year at a mortality rate of 13.6 deaths per 100,000 climbers, it follows that the expected number of deaths would be 5.4 per year.

It is routinely stated on various Kilimanjaro sites that there are approximately 10 tourist deaths per year. However, there is no evidence to support this figure.

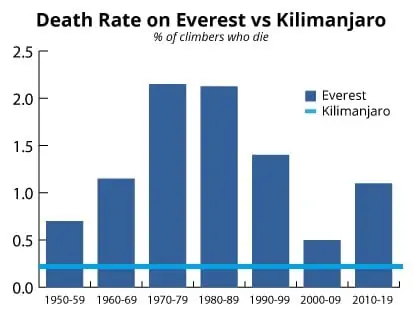

Put another way, 0.014% of people climbing Kilimanjaro may die. By comparison, according to the BBC as of 2018 less than 1% of all climbers attempting Mount Everest died. On average, about 1,000 people attempt Everest a year. However, the 2019 Everest climbing season took 11 people’s lives. Which pushed that percentage over 1.1%.

What these statistics point out is that climbing Kilimanjaro, as with any ascent of a seriously tall mountain, is inherently a dangerous adventure. Problems are exacerbated by the fact that Kilimanjaro is possibly the easiest mountain of such a size to scale, with no actual climbing involved – which attracts more people of all levels of fitness, whether they are of a suitable physicality to climb such a large mountain or not.

However, the Hauser paper stated that of the fatal cases that were examined, most could have been prevented.

HOW TO STAY SAFE ON MOUNT KILIMANJARO

What can a climber do to safeguard against being a statistic?

First of all, to begin your preparation it’s essential to train adequately for your expedition. To be in great shape means your body will be able to better tolerate the effects of altitude and exercise. Secondly, if you have known medical conditions or are of older age, you should see your doctor and get cleared for high altitude trekking. Being at high elevations can trigger health complications in those who have pre-existing conditions. Third, every climber needs to be familiar with the typical symptoms of altitude sickness. When you are on the mountain, be very honest about what you are feeling so the guides can take corrective action.

Besides these, you should climb with a Kilimanjaro operator that has guides that are medically trained to keep you safe. The best Kilimanjaro operators have extensive safety programs in place to monitor and treat clients throughout the trip. At Peak Planet, your safety is our number one priority. We have many layers of safety built into our operations to minimize the risks on Kilimanjaro. No other climbing company provides such a comprehensive safety program.

- Our guides are certified Wilderness First Responders (WFR)

- Our training and safety program was developed by IFREMMONT, a European-based high altitude medical training organization

- We have established protocols for handling emergencies on the mountain

- We conduct twice daily health checks using a pulse oximeter and stethoscope to measure pulse, temperature, blood pressure and oxygen saturation

- Our guides are equipped with Garmin inReach Explorer, a satellite communication device, for real time location tracking and communication

- ALTOX Personal Oxygen Systems, which reduce the likelihood of altitude sickness, are available for rent

- We carry emergency oxygen on all climbs to combat serious cases of altitude sickness

- We carry portable stretcher to quickly evacuate climbers who are unable to walk on their own

- We carry first aid kits to treat minor injuries such as blisters, cuts and abrasions

- We can initiate helicopter evacuation through Kilimanjaro Search & Rescue for severely injured or ill climbers

Our guides perform health checks twice per day for each climber. These evaluations are very thorough but necessary to ensure that everyone is acclimatizing to the increasing elevation and staying healthy. The data is logged and reviewed each night.

The health checks include:

- Taking body temperature: We use an infrared thermometer or armpit thermometer.

- Checking blood oxygen saturation: We use a pulse oximeter that attaches to a finger to monitor your blood oxygen saturation.

- Measuring heart rate: We use a pulse oximeter to also measure your heart rate.

- Taking blood pressure: We use a blood pressure monitor that is attached to the wrist.

- Listening to lungs: We use a stethoscope to listen for healthy functioning of the lungs.

WHAT ARE SEVERE FORMS OF ACUTE MOUNTAIN SICKNESS (AMS)?

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), sometimes called altitude sickness, is an illness caused by ascent to a high altitude and the resulting shortage of oxygen. AMS is the number one reason people come down off the mountain before they make the summit. Though most people will experience mild symptoms of AMS, there are a couple of rare but severe forms of AMS that you should be aware of, HAPE and HACE.

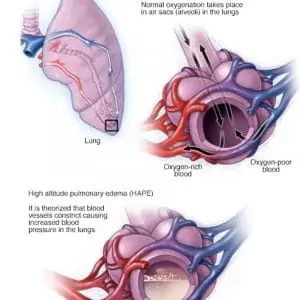

HIGH ALTITUDE PULMONARY EDEMA (HAPE)

What is High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) and how do you avoid it? HAPE is a life-threatening form of non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema, which is fluid accumulation in the lungs. This can occur in otherwise healthy mountaineers at altitudes typically above 8,200 feet. However, cases have also been reported at lower altitudes such as 4,900–8,200 feet in highly vulnerable subjects.

Studies have not been able to pinpoint what makes some people susceptible to HAPE. HAPE remains one of the major causes of death related to high-altitude exposure. There is a high mortality rate if you do not get immediate treatment.

Symptoms of HAPE (You need at least two):

- Shortness of breath at rest

- Cough

- Weakness or decreased exercise performance

- Chest tightness or congestion

In addition to:

- Crackles or wheezing (while breathing) in at least one lung field

- Central blue skin color

- Tachypnea (rapid breathing)

- Tachycardia (rapid heart rate)

An individual’s susceptibility to HAPE is difficult to predict. The most reliable risk factor is the previous susceptibility to HAPE. There may also be a genetic predisposition to the condition. People with sleep apnea may also be more susceptible due to irregular breathing patterns while sleeping at high altitudes. Studies have shown that HAPE occurs in less than 1% of climbers exposed to altitudes above 13,000 ft.

The standard—and most important treatment—is to descend to a lower altitude as quickly as possible. 400-500 feet is preferred. Oxygen should also be given if possible. Symptoms tend to quickly improve with a descent. While more severe symptoms may continue for several days. Also, drug treatments are available.

The U.S. Army has conducted tests for over 30 years. They performed these studies by exposing sea-level volunteers rapidly and directly to high altitudes. Of the 300 volunteers, only three had to be evacuated due to possible HAPE.

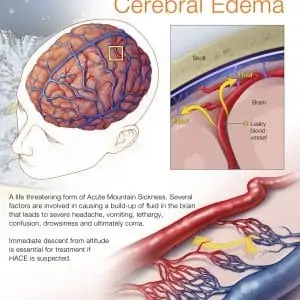

HIGH ALTITUDE CEREBRAL EDEMA (HACE)

Another risk climbers take is getting High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE). HACE is a severe and sometimes fatal form of altitude sickness that results from capillary fluid leakage. This is due to the effects of hypoxia on the mitochondria-rich endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier.

Symptoms include:

- Headache

- Loss of coordination (ataxia)

- Weakness

- Disorientation

- Memory loss

- Psychotic symptoms (hallucinations and delusions)

- Coma

Cerebral edema can result from brain trauma or nontraumatic causes. These causes can range from ischemic stroke, cancer, or brain inflammation due to meningitis or encephalitis. But with climbing, it is due to fast travel to high altitude without proper acclimatization. Four types of cerebral edema have been identified: Vasogenic, Hydrostatic Cerebral Edema, Cytotoxic, and High Altitude Cerebral Edema.

HACE generally occurs after a week or more at high altitudes. If not treated quickly, severe cases can result in death. Immediate descent by 2,000 – 4,000 feet is a crucial life-saving measure. Medications such as dexamethasone can be prescribed for treatment in the field. Proper training in their use is required.

Therefore, anyone suffering from HACE should be evacuated to a medical facility for proper follow-up treatment.

HOW DOES PEAK PLANET HANDLE EMERGENCIES?

Peak Planet is well prepared to manage crises on Kilimanjaro. We have established protocols for every type of situation and for every location on the mountain. If an emergency were to happen, our teams know exactly what to do, step by step. We carry the necessary medical equipment and a complete first aid kit to handle emergencies on the mountain, including climbers who have been stricken with HAPE or HACE. Below is a list of the items we carry on all climbs.

EQUIPMENT

- Pulse oximeter

- Sphygmomanometer (blood pressure monitor)

- Digital thermometer

- Stethoscope

- Portable stretcher

- Oxygen bottle and mask

- Portable Altitude Chamber (on Northern Circuit treks only)

FIRST AID KIT

- Rolled gauze

- Gauze bandages

- First-aid cleansing pads

- Butterfly strips

- Iodine

- Medical gloves

- Paramedic sheers

If the need arises, and it doesn’t happen very often, our guides can coordinate rescue and evacuation with other staff, the park service or Kilimanjaro Search & Rescue (helicopter service). Each trekking party carries an Garmin InReach satellite communication device. It allows our guides to get in touch with the necessary parties from anywhere on the mountain. Kilimanjaro SAR evacuation is a service we offer to take injured or sick climbers off the mountain when situations are severe.